Erich Maria Remarque and the Art of Living

A rumination on Remarque’s lasting legacy on the power of finding happiness in the midst of hardship and an ever-changing landscape.

Time to read: 5 min.The Unstoppable Undercurrents of Time

Living has yet to be generally recognized as one of the arts, professed Karl De Schweinitz in his insightful 1924 study “The Art of Helping People Out of Trouble.” As a key component of mastering the art of living, De Schweinitz identified the ability to gracefully adjust oneself to life’s unpredictable events and circumstances, which “come towards us one after another” (almost half a century later, flexibility and adaptability would be officially recognized among the principal 21st Century Skills, deemed just as imperative for success as critical thinking and financial literacy).

Man, asserted De Schweinitz, is not born into a world made to fit him like a custom-tailored suit of clothes or a house built to order. He enters a universe that was eons old before his appearance…[an] eternally changing universe that evolves its processes unmindful of his presence. It sets the conditions. It is man who must do the fitting.

Navigating life’s bumpy roads has been a central theme for another astute mind, a contemporary of De Schweinitz—that of German novelist Erich Maria Remarque (1898-1970). Drawing from personal experiences, Remarque’s works present a compelling case for maintaining flexibility in an ever-changing and often threatening world without losing one’s sense of wonder at its beauty, however ephemeral. This painful realization—that each human experience comes with an expiration date—makes Remarque’s writing one of the most unconventional invitations to be fully alive.

Regret is the most useless thing in the world. One cannot recall anything. And one cannot rectify anything. Otherwise we would all be saints. Life did not intend to make us perfect. Whoever is perfect belongs in a museum.

Arch of Triumph

In recalling some of Remarque’s major works I fell in love with in my early twenties (ah, the psychologically convoluted characters swept by events they have little to no power over, the ever-doomed romance, the ritualistic nocturnal consumption of calvados or whiskey or brandy or wine or any liqueur really, and, of course, the melancholy reflections of life and the passage of time!), I could not overlook his acute relevance in our time’s obsessive quest for perfection and lasting happiness — which are but self-deceptions, as this pandemic has reminded us once again.

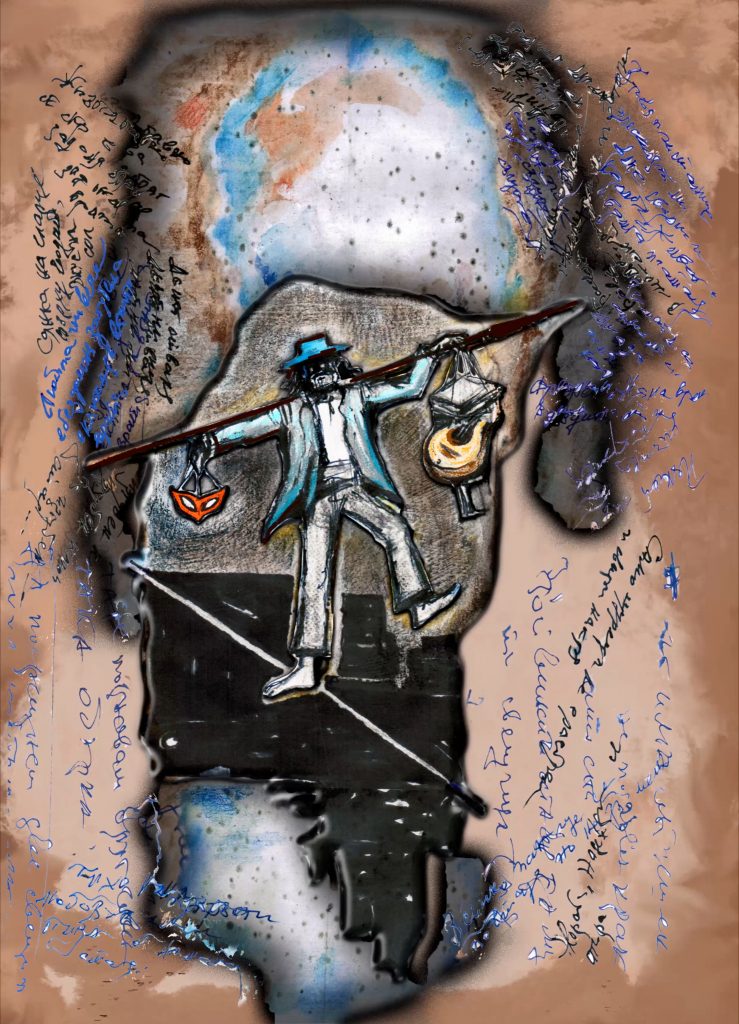

Because what else are we, if not imperfect beings, operating in a rather imperfect world? Balancing on the tightrope of life right above the abyss. Making difficult choices, often with unknown outcomes. We fall. We fight. We rise. We inevitably fall again. We bounce back and fight once more. And so it goes on and on. I can’t help but think (keeping in mind the imperfect beings we humans are): struggling to find balance in an imperfect world, perhaps we should cease trying to be lastingly happy altogether and aim just to be.

This clash between man’s expectations and experiences was beautifully articulated by one of television’s most exciting recent characters, the mythological Viking Ragnar Lothbrok. Echoing voices from all of Remarque’s leading protagonists, Travis Fimmel’s character articulates the essential difference between chasing conditional what-ifs and embracing life’s complexities by living in the present—a distinction we often miss, fixated on life’s semantics rather than its syntax.

What does happiness mean, anyway? Can we apply a strict definition to our convoluted lives? Is there an equation for quantifying happiness, or should we accept that, in reality, unlike in theory, two plus two always equals five?

Perhaps, happiness means to dance above the abyss.

Heaven Has no Favorites

With his uncanny ability to capture and chronicle life’s subtleties, Erich Maria Remarque mapped the rugged terrain of men’s quest for meaning. The author himself was a man of not a few contrasts in his own storied life, marked and accentuated by an impoverished childhood, the loss of loved ones, two devastating world wars (he was wounded in the first one and prosecuted during the second), extravagant habits, a plethora of affairs and heartbreaks, all mixed with sudden bouts of deep depression. And yet, Remarque would manage to retain his integrity and appreciation of life, a testament to his wisdom, leading us to believe that “the miracle is always waiting for us around the corner of despair.”

Remarque in a Nutshell

Born Erich Paul Remark on June 22, 1898, in Osnabrück, Germany, he was the third of four children in a lower-middle-class family. The young Remarque, a gifted pianist, gave piano lessons to afford books and other necessities. Influenced early on by Dostoevsky, Goethe, and Stefan Zweig, he began crafting poems and essays at sixteen.

When World War I loomed, the eighteen-year-old Remarque, a student at the University of Munster, was drafted into the military and sent to the Western front along with his peers. Bad shrapnel injuries he sustained there put a halt to his aspirations of becoming a concert pianist, a dream further shattered by his mother’s death from cancer the year before (in her honor, Remarque would change his middle name to Maria). Still, as we are continuously reminded throughout our lives, getting lost is often the best way to wind up exactly where we are supposed to be. Determined to improve his circumstances, he worked various jobs—journalist, salesman, musician, race-car driver—experiences he would subsequently draw upon in his novels.

[Aubridged from Argent’s 2021 Infected issue.]