Clam Diving in Karadere

This rhythmic pounding was in fact the first sign of trouble—the water was not calm, but rather choppy, dark, and taciturn...

Time to read: 13 min.We headed out from Byala in a bright orange UAZ-KA (the Soviet Union’s all-terrain vehicle now ubiquitous throughout much of Eastern Europe) with “SAFARI” written grandly across the door. We were hoping to scrounge up some dinner. Our destination was Karadere beach, and our prey were the local mussels—midi in Bulgarian—that enjoy the relative comfort of its rocky shores.

While at dinner two evenings previous Toshko—a real estate maverick known for selling big resort properties along the Bulgarian seacoast– mentioned the possibility of mussel gathering at Karadere. After expressing my eagerness to try it, he had been kind enough to set the whole thing up; make the proper arrangements, as it were.

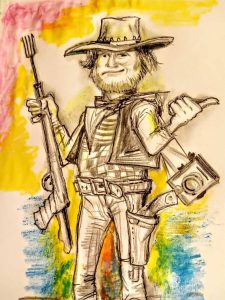

And so it was with a certain enthusiasm I grabbed my principal partner in crime Dimitar (A.K.A. Mitko), and we headed out under Toshko’s capable leadership. Mitko is an engineer and IT tech. He has shock white hair and wears glasses. In the winter, when he grows out his beard, he could be Ernest Hemmingway’s double. Toshko is a fit, lean man in his sixties.

After driving a short distance we left Byala—a town known for its white cliffs (hence the name “Byala,” or white) and dinosaur bones—and turned off the road onto a dirt path. The driver threw the UAZ into low gear, and soon we were rumbling through cultivated fields stretching far into the horizon. Our driver was typical; meaning, he fit the mold of most drivers I have come across in my travels – talkative, chill, with an all-around sense of ease on just about any conversational topic, tinged with a heavy dose of pessimism. Because it was the only language that all of us collectively spoke, we chatted in Russian as the UAZ bounced and grinded over the uneven terrain.

Another turn, this time down a steep, grooved hill. I grabbed onto an overhead bar to keep myself from tumbling from the back of the UAZ. The vehicle stabilized, and we rolled past a vineyard, one of the many the region is quickly becoming known for. A vast pool of what looked to be blue-black ink opened up before us – the Black Sea.

I was staring at one of the last undeveloped territories along the Bulgarian coastline.

At the bottom of the hill I could see a stretch of beach, along which were a long line of tents, trailers, and mini-compounds of various sorts and sizes. Some of them had achieved certain aspects of constancy: crude, hand-made wooden fences along their perimeters, camouflage nets, awnings which cast long, angled lines of shade under the blistering sun.

Karadere, long a summer destination for Bulgarians wanting to escape jobs, city stress, or simply to “unplug,” has in recent years taken on certain political nuances. In 2008 there were plans to develop a series of eco-friendly, automobile-free, self-sufficient villages supporting up to 15,000 inhabitants. The project was developed under the guidance of Norman Foster, a prolific British architect known for his international high-tech constructions. There was, and still is, a significant amount of pushback from certain environmental and intellectual parties. Many fear that the development will make Karadere an exclusive resort for the rich. Several top-level Bulgarian politicians – including the Prime Minister – assert that there is nothing illegal about the proposal. The one billion euro project stalled in 2009 for lack of investment.

As we drove along the beach I could at once sense an anti-establishment vibe. Time seemed to slow; there was absolutely no bustle. Fragments of imagery swam past. A half-nude woman hanging laundry, make-shift tables next to told campers, swimmers tossing around a ball in the surf, makeshift toilets, a photographer snapping pics of wildlife.

It was quiet.

Disembarking, the driver silently handed us down our gear, then hopped back in the UAZ and was gone. For the next few hours we would be stranded.

I had a thought, quite in line with my-at-times morbid sense of imagination: what if these people all belonged to some strange sect, thought of us as outsiders infringing upon their territory? What if the people here were cannibals, half- starved and eager to put us in pots and devour our flesh? How could we be sure we would make it out of there alive?

I looked around. The bland, even bored faces we passed showed little enough interest in engaging in cannibalism. The odds of us ending up in pots for the moment seemed statistically insignificant.

We moved purposefully down to the far side of the beach where a conglomeration of boulders sat stubbornly accepting the incessant crashing of the waves. This rhythmic pounding was in fact the first sign of trouble—the water was not calm, but rather choppy, dark, and taciturn.

My earlier vision of walking in placid knee-high waters surrounded by clams easy for the picking was at once shattered. Indeed, our task—as I soon found out—was to snorkel in amongst the rocks, periodically dive deep into the water to search for the tasty clams at the bottom of the sea, all while waves thrashed into the rocks around us.

I looked at Mitko, perhaps for guidance, or something… I’m not exactly sure what. He was nonchalantly taking his shirt off, busy getting ready for a sunbath. He stopped long enough to give me a look, which seemed to say, “you got yourself into this shit, now live with it.”

Toshko, meanwhile, had cracked open a can of beer. He passed two more around. After a quick “Nazdrave!” he went about unraveling his kit with practiced, methodical intent. Slipping on gloves and a snorkel mask that put my 15 Leva kit to shame (I had bought it at one of the ubiquitous kiosks which sell cheap swim gear and souvenirs.) Toshko then donned a pair of what looked to be professional-quality fins. For my part, I had opted for hiking shoes.

Together, we waded out into the dark, frothy waters, little comment passing between us.

Toshko and I swam, occasionally diving down into the murky waters, all the while getting pushed around by swirling currents. I took a deep breath from the stale air in my snorkel tube, dove down to the seafloor. A small crab scuttled past. I thought about reaching for it but thought better of it. Too small to be of any use.

Time and again we dove, searching underneath the rocks where the creatures supposedly dwelled.

We didn’t see one clam.

Surfacing together in amongst a smattering of boulders, Toshko said in half-Russian, half-Bulgarian, “This area has all been picked clean. Nothing here.”

I nodded, remembering all those campers on our drive in.

For my part I remarked, “Yeah, “And every one of those people,” I pointed toward the stretch of beach, “probably knows it.”

As we were talking Toshko had perched himself on a large boulder. At about that time a big wave came crashing in, knocking him off. I thought for a moment he might have been hurt. All around him were rocks, sharp and jagged. Later I would find out just how sharp after being pushed into one by a particularly gnarly wave, scraping and cutting my knee bloody. Toshko, though, porpoise-smooth, turned onto his back, motioned for me not to worry, and swam out of danger, his legs kicking behind him like a fluke, eyes focused underneath the fog of his goggles.

But we had both taken note of the danger. A few minutes more and we’d had enough. Fighting the current, we headed back to shore. We splashed out of the surf back to where Mitko was watching us and enjoying his beer. He squinted meaningfully as we clambered up to him.

Expanding our lungs with deep gulps of hot, salty air, we took respite, though the sun was merciless. After a few moments rest, Toshko said we might do better at Tsar’s beach–a less frequented shore located a short hike up the hill and through the Karadere woods.

“We have time. Do you want to try it?” he asked.

“Absolutely,” I said, trying to put some snap into my voice.

“Mitko, we’re going to head up through the forest and curve around to Tsar’s beach.”

“Okay,” he said.

“You coming?”

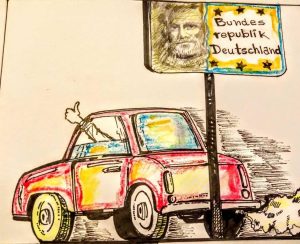

“I’ll stay here,” he said. Again that meaningful squint. It was evident he wanted to be alone. This beach was special, after all. He had been coming here, like Toshko and the others now camped in their campers and tents beside us, for decades. As a young man he had milked wild goats in the mornings and observed the dance of dolphins at dusk. Had even brought his infant daughter here, in his famous Trabant, the ancient German car that could do anything, go anywhere…

While we were hunting clams, he would be doing more important things: tumbling old memories over in his brain, savoring each one of them, re-living them. How is it that time moves forward so swiftly? How is it that just yesterday she had been holding tightly his fingers, laughing and giggling in the waves, and now, today, she was a woman grown, full of agency and purpose?

We left Mitko to his contemplation and hiked our way up the hill, threaded our way through the forest. At times eerie, the wood is an ancient place, full of cracked boulders and twisting roots. White butterflies flutter in nature-made bowls of earth, all the while horse-eaters gnaw at your neck. The place looks for all the world like something out of an Astrid Lindgren fairytale. That is, accepting the clots of toilet paper beachgoers have left along the trail after doing their business.

Bits of tissue notwithstanding, traveling through this forest one gets a sense of what all that development along the Bulgarian sea coast has destroyed, and I could see why people wouldn’t want something like this tampered with. Would want, for all the world, to preserve it.

Stepping down another series of steep declines (fortunately, someone had taken the considerable time to carve rudimentary steps into the earth, making it easier for us to descend) we reached Tsar’s beach. It is a hidden gem and there was not a soul in sight.

Like sub-mariners preparing for a mission, we began getting out our gear, still intent on making a go at a clam dinner. We were either going to come back heroes or villains. I steeled myself, took a deep, courage-inducing breath. “Shit,” I said. “I forgot my…” I held up one of my hands and wiggled my fingers, for I’d forgotten the Russian word for gloves. Toshko nodded, said the Bulgarian word. He had also forgotten the word in Pushkin’s tongue.

“It’s okay,” he said, “I’ve got another pair.” I should mention here that Toshko, prior to becoming involved in real estate, was a soldier and a fireman. He is the type, I suspect, that knows the importance of not leaving gear behind. His preparedness had saved me from clam hunting without proper hand-wear.

The rocks were brutal on my bare feet, and I ambled oddly forward, a foreigner in a foreign land in an otherworldly dance. Each step was followed closely by an internal string of curses as I felt each stone dig into the soles of my feet, but I was propelled forward by the image I had in my head of my wife’s disappointed face when she learned we’d come back empty-handed. Toshko seemed not to be bothered in the least. I slipped my shoes on, dropping quickly into the water, letting the pull of the surf draw me out. Just before pulling the mask over my face, something bubbled up from the recesses of my subconscious: “Perchatki,” I said, finally remembering the Russian word for glove.

“Perchatki, da da,” Toshko agreed. And then we were at it again.

But the mussels still proved elusive. Time and time again we dove, to no avail. The water was still choppy, and as the sea tossed us about, the earlier issues on the rocks were still very much on our mind. It was a wearying effort. The diving, the hike—not to mention the linguistic perambulations—had drained us. A few minutes more worth of snorkeling, back ashore for some picture taking, and we were on the trail once more, treading our way back through the woods toward Karadere.

Halfway through the forest we stopped to look at an old site where Toshko remembered camping a couple of decades earlier. I could see the place had real significance for him. I waited as he looked around, soaking everything in, absorbing it down to his very bones. “In the old days,” he explained, “the trees were not so overgrown, and one had had a clear view of the sea.”

We headed back down the trail.

When we got back Mitko was snoozing under his umbrella, legs covered in beach gnats but none the worse for wear. Resigned to our clamless fate, we all decided to head to the center of the beach and wait for the driver’s return. Making like the natives we jumped into the water for a good long relaxing swim.

A little while later I clambered out of the sea and sat on the beach, letting the sun and the breeze dry my body. Mitko emerged next, half-fell as the waves pushed him drunkenly forward out of the surf. Toshko, still using some reserves of energy I couldn’t fathom, continued to swim.

There was a group beside us, two men and two women. I thought they might be related but I couldn’t be sure. The elder male was laughing as he swam, taunting the others as they threw stones at him playfully. The woman, perhaps the man’s wife, in due time stripped off her swimming suit and swam in after him in the nude. The man continued to laugh.

Toshko, ever alert, said, “he’s here.” I looked back. Indeed, there could be no mistaking our bright orange UAZ-KA as it wound its way down the beach. Our time at Karadere was at an end.

A little while later, back at Byala, hot, sweaty and dirty, Mitko and I sat down for some much needed beers. I looked at him. “That was good,” I said.

He looked at me, gave me that slight nod of the head, the way he always does it, all the while wearing a shit-eating grin, and in whispered English said, “experience.”

Yes, I thought. Experience.