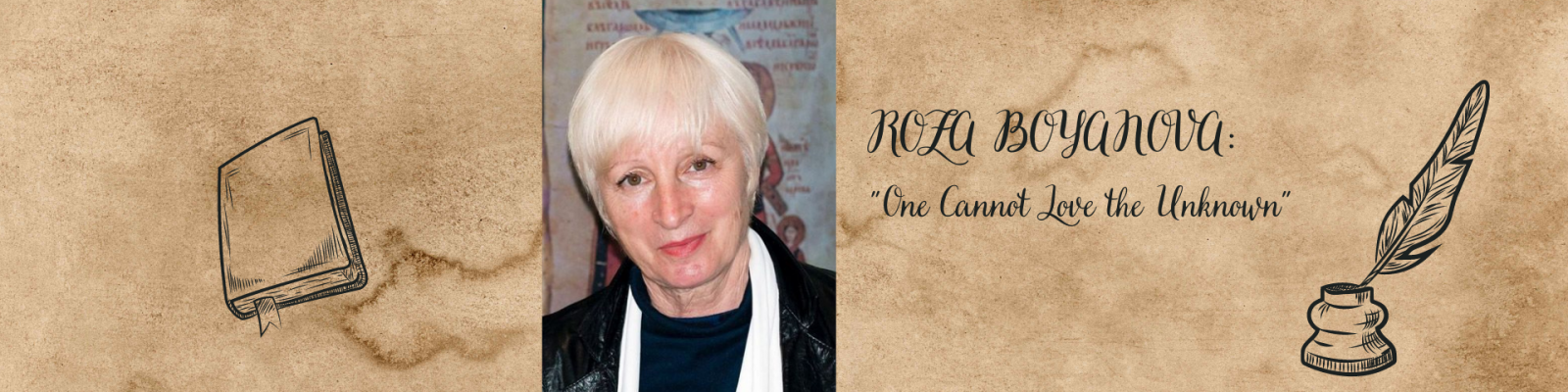

Roza Boyanova

"One Cannot Love the Unknown"

Time to read: 5 min.Roza Boyanova, an author of 16 books of poetry and essays, has made significant contributions to the literary world of Bulgaria. Her debut book, “Thirsty Water,” earned her the National Debut Prize “Vladimir Bashev.” In 2007, Boyanova received the national lyric prize “Ivan Peychev” for her poetry collection “Distant Diptych.” Her poems have been translated into numerous languages, including English, Russian, German, Ukrainian, Greek, Turkish, Polish, Croatian, and Romanian. In the 1980s, Boyanova established the first literary studio for talented children in Shumen, serving as a creative laboratory for discovering, nurturing, and showcasing young talents. She is an honorary citizen of her native town, Burgas. Earlier this year, Boyanova presented her poetry collection “Reverse Gravity” in Shumen.

The regional library in Shumen, where you recently showcased your poetry collection, attracted a dedicated but relatively small audience. Why do you think the literary space has been shrinking in Shumen and Bulgaria, in general, but also globally in recent years?

The gathered audience of friends and poetry enthusiasts was not insignificant. I have attended presentations featuring intriguing authors where only five to ten people were present. This number doesn’t diminish the importance of the literary event. However, it is disheartening that so many people miss out on the joy of connecting with another soul, experiencing a unique perspective on language, and uncovering the core of an author’s work. Each literary creation is a treasure, yearning to be shared; it resonates with the reader’s experiences while evoking new emotions that transform and provide spiritual gratification—similar to my experience when reading exceptional poetry.

While in Shumen, you expressed your desire for literature to reclaim its rightful position among other arts, though this seems unlikely today. Do you think the rapid development and flourishing of music, cinema, and multimedia communication on the internet created this barrier, or is it something else?

One cannot love the unknown, just as one cannot determine if one like the taste of an unfamiliar fruit. Poetry must be read to cultivate an artistic taste and subsequently find joy in the words that may already exist in their vocabulary but have never had such a profound impact. The other arts can only amplify the beauty of poetic expression. However, internet communication is not just poetry; it encompasses thousands of ways also to despise words.

What literary games would you suggest for children captivated by poetry and prose?

One simple yet engaging literary game is “What is…?”. You ask for a noun, and the answer should come in the form of a comparison, albeit without using the word “like.” This game has roots in Old Bulgarian literature and later appeared in the works of P. R. Slaveykov. Inspired by Odysseus Elytis (“Open Cards: Reflections”), we adapted the game by defining its rules and broadening its scope. Examples from such a game include: What is a nest? – A beggar’s crumb; What are icicles? – Earrings on roofs; What is a sparrow? – Cotton candy on two sticks.

When working with students in literary pursuits, preventing them from merely replicating their teacher is crucial. How do you ensure your young students do not imitate your stylistics, poetics, and literary identity?

The younger students typically write in classical verse, producing rhymed and rhythmically well-structured works. As they mature, they become familiar with various techniques and styles, experimenting with them all. I promote diversity in writing. The authors themselves are mindful of influences, striving to avoid imitation.

Metaphors and metaphorics play a significant role in your poetics. Why have you chosen to rely on them?

The enduring presence of metaphor in poetry, from the Ancient East to the present day, attests to its beauty. This holds true, whether we interpret metaphors today as initially intended or discover new meanings and connections that transport us beyond the visible and concrete. It may seem improbable, but I have also observed some metaphors manifesting in life. Consequently, we must be cautious with our words. Everything spoken eventually becomes a reality – metaphors in a literal sense and experiences with artistic justification.

Poets are often accustomed to exploring their inner world, the landscape of the soul. Does this make the extraordinary situation of being confined to their homes [due to the coronavirus lockdown] easier for them?

If they enjoy what they uncover within themselves and do not find their own company tiresome, it can be pleasant to delve into their own secrets and depths. However, if they are used to living according to the perceptions of others and seeking external validation, they may struggle with their unmasked and unadorned reality. Writing is inherently a solitary activity, with authors immersing themselves in the lives of their characters while they write. It’s less likely that they would feel bored by the freedom of solitude. But who can truly say?

Your latest book has already been printed and is published by the Zahariy Stoyanov Publishing House. What is its title, and how did it come into existence?

The title is “ALTO: The Verses That Chose Me.” To avoid misunderstandings, during its presentation in Burgas in February, I added: “The Voice with Which I Speak to You: ALTO.” Two years ago, I received an invitation from Ivan Granitski, the director of the Zachary Stoyanov Publishing House. I chose my compiler, Ivan Bregov, a friend and fellow member of the Literary Studio “Mythical Birds” in Burgas. I asked [the late] Rumen Mihaylov to be my artist again. He and his wife, Lidia, visited Burgas and presented me with two watercolors. “This is ALTO,” they said, and I agreed. It saddens me that Rumen could not see the finished book. It was published after he had followed his “Vibrations of the Soul” and passed away. He must be somewhere there – among the cosmic visions he shared with us in his other exhibitions.