The Classical Revolution of Glenn Gould

Just like many fictional superheroes, he possessed genius of a quality that few were able to comprehend

Time to read: 7 min.As hard as it is to believe, there are actual, real-life superheroes. Individuals whose talents surpass anything most of us could ever dream of. These are humans with extraordinary, other-worldly abilities who can do things – achieve feats – that over time raise them to the level of a superhuman.

Glenn Gould was one such individual.

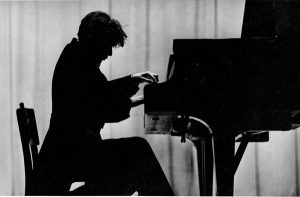

In 1955 Glenn Gould, when he was only twenty-two years old, recorded the Goldberg Variations, a visionary work that re-imagined the music of Bach. Gould played the Goldberg Variations differently, to say the least. He played them with speed, with electricity, with a technical, machine-like ability hitherto not associated with the liturgical Bach. In North America, he became a sensation overnight.

Undoubtedly, Gould was a prodigy with immense talent; someone who the at times dour musical world had no choice but to take notice of. His interpretation and re-interpretations of Bach are still marveled at today, over three decades after his death.

Just like many fictional superheroes, Glenn Gould possessed the genius of a quality that few were able to comprehend. Even professional musicians, themselves masters of their craft, had difficulty conceptualizing his virtuosity from a technical and theoretical point of view. And what was more, he reveled in the mystery surrounding himself; a mystery that grew in proportion and over time approached myth and then, finally, legend.

He revead too in the many rumors swirling around him. Rumors of his health and his asexuality, all of which he encouraged because he was able to use them as a shield thrown up between the world and his precious privacy. These rumors allowed him to remain opaque and inscrutable to the outside world. He became a mysterious recluse; someone who even his friends rarely saw or encountered other than through a phone receiver during a late-night, impromptu call.

In 1957, following his successful recording of the Goldberg Variations, Gould toured the Soviet Union. He was little known in Moscow or Leningrad, but Gould flew in like a cosmonaut, wowing the Russian audiences with his magnetism and virtuosity.

And then, just a few years later, in 1964, at the age of 31, he suddenly disappeared from the concert tour, rebelling as he did against the grueling schedules, the endless travel, the unfamiliar pianos and climates, and the disapproving conductors who disagreed with his vision. In one famous instance, Leonard Bernstein offered a disclaimer to concert-goers, going so far as to say he disagreed with Gould’s playing but was committed to conducting all the same. (such a statement made by a conductor expected to work in unison with a performer was something unheard of) The press had a field day.

But Gould was his own man. He was just getting started. He would play the way he wanted to play, others be damned. He wasn’t afraid to no-show either, often canceling more concerts than he showed for.

Not to mention the host of idiosyncrasies: the overcoat in summer, the gloves that he almost never took off, the bottles and bottles of pills to deal with his multiplicity of health concerns. Glenn Gould was a force to be reckoned with, and in time the myths surrounding him would only grow.

In the end, concert life was simply incompatible with the life of this solitary, private genius.

In the years to follow Gould would take his musical and artistic career in a decidedly different direction, moving instead into the realm of broadcasting, documentary film-making, composing and conducting, or spending thousands of meticulous hours in the studio producing new recordings.

Over time he became consumed with using his intellect and what was technologically possible to disassemble and re-assemble various compositions, reinterpreting them in ways not previously imagined. Before Gould, music in the classical world was played rather dryly, in the same traditional way it had been played, time and time again, from Bach to Beethoven to Mozart. Gould wished to change all that. He believed that if one was going to play a piece of music, then one should bring something new, something that would stand out from the rest. Music was not meant, he thought, to be static, and often times he made note of the fact that composers themselves provided for variations in their compositions. And if this was the case, why shouldn’t conductors and musicians re-imagine these works in their own distinct, original ways? It made things, in his view, much more interesting.

Gould had a strong desire to make others understand his point of view and musical intentions. He wanted to be seen as a creator, as first and foremost a revolutionary in the world of music.

He was not easy to work with. Not at all easy-going. But this is the way of geniuses wholly consumed with their art. He was exacting. He would work late, often until two or three in the morning, and he would not stop until he had achieved the sound he wanted to achieve, in every minute detail. And perhaps most amazingly, he played completely from memory, without notes or sheet music of any kind. His focus was excruciating, his memory prodigious.

But there was a part of him — and this is the part of him that I am most fond of, that refused to take himself too seriously. A part that preferred so often to err on the side of playfulness.

I love to watch his interviews, both those in his early career that had not been staged, and then later, those that almost always were scripted. They tell so much about him and speak to his intellect, his need to separate himself from the world with a shield of solitude and prearrangement. And then there was the list of nonsensical characters — Sir Nigel Twitt-Thornwaite, for instance — that he created and used to act out comedic skits.

Watching these, I think almost that it is a shame he could never quite settle himself or form a family, could never quite get a handle on his own hypochondria, for he would have made a wonderful and impressionable father.

Listening to Glenn Gould play has always done something to me. His interpretations are always so moving and fresh, even today. They have the ability to awaken and access the deeper layers of psychic substrate. They are soothing and yet also somehow quite sad. They contain within them Gould’s understanding of the essence of unrealized yearnings. Listening to Gould’s recordings is a reflection upon the act of feeling.

Glenn Gould was obsessed, one may say, with keeping aspects of himself hidden away from the world, but he also wanted to be heard; wanted his presence to be felt.

And although he was difficult and quirky, and never quite fit in (and never wanted to), for a brief moment he let us all in; gave us some amazing music, and made us feel what life and existence meant for him, before departing from this world at the age of 51.

Genius — though it is a term thrown into the air casually these days — is such a rare thing. To see it manifest before you in the mind and body of one man is remarkable.

Looking back on his life, it is possible he was overwhelmed, bowed beneath the weight of his own superhuman abilities. They perhaps left him bereft of something vital. There was a tempest of creativity raging within him, and he could never quite control it; could stymie it perhaps only with his quirky humor and a plethora of idiosyncrasies and a bevy of pills. His genius, as it so often does to prodigies, drove him and, finally, completely exhausted him.

We are fortunate to have his recordings, and the world is a better, more interesting, indeed more musical place, as a result of his having lived in it.